Exploring the Uncanny Valley in Robotics and Culture

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding the Uncanny Valley

The concept of the uncanny valley is a captivating topic within robotics and popular culture. In a recent essay, I reflected on my journey as a landscape architect, where I learned about the importance of originality in design. A key takeaway was that a design that nearly succeeds can often be more perplexing than one that completely fails. An experienced architect once remarked, “I can see your intention, but this simply doesn’t work.” This “almost there” feeling creates a unique type of cognitive dissonance.

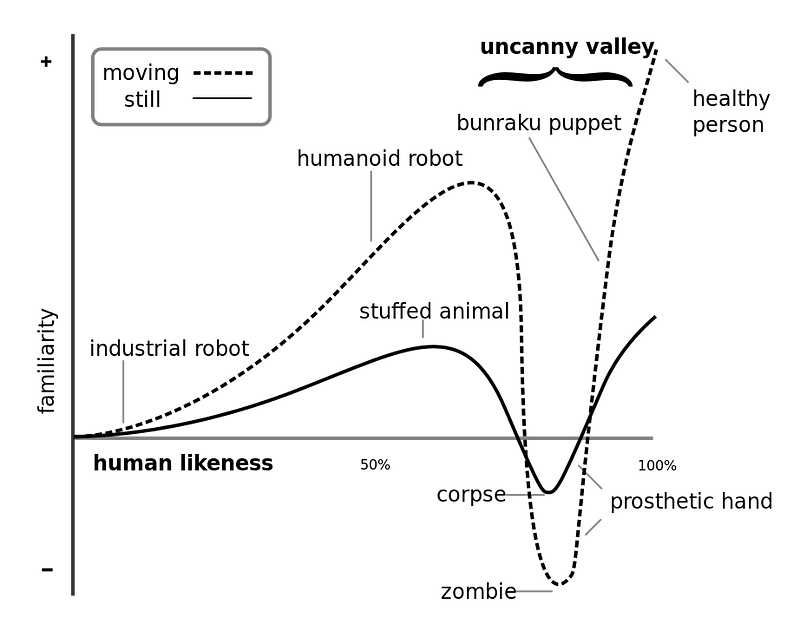

Even when we can’t pinpoint the exact issue, we instinctively sense that something is off. This is especially true in robotics. The term “uncanny valley,” coined by Japanese robotics expert Masahiro Mori in 1970, describes our emotional response to humanlike robots. Mori proposed that as a robot’s appearance approaches but does not fully achieve realism, our feelings may shift from empathy to discomfort. This phenomenon encompasses a variety of near-human forms: puppets, clowns, realistic animations (such as the film Polar Express), mannequins, prosthetic limbs, false teeth, wigs, wax figures, masks, and, of course, robots.

Mori did not provide definitive explanations for this reaction, but he hinted that it might relate to our instinct for self-preservation. A humorous example illustrating this aversion comes from a story by the late comedian Jerry Clower. He narrated a bizarre tale of a man who trained a monkey to hunt raccoons with a pistol and flashlight. Upon encountering another raccoon hunter, the man exclaimed, “Get that thing away from me! It looks too much like a person!”

This aversion extends to various quasi-human figures: from Frankenstein to zombies and even the Terminator. They evoke discomfort because they are close enough to humans yet sufficiently different. The same unsettling feelings apply to clowns, giving rise to the term “coulrophobia,” which describes the fear of clowns—a condition not formally recognized in the DSM-V.

As I recently recognized, I’ve been delving into the uncanny valley through an ongoing photographic project titled The Goodwill Doll Head Project. I established a set of rules for this project: the dolls had to be sourced from a Goodwill store, photographed as I found them without posing, and captured in a close-up style reminiscent of fashion photography. This project explores the implied sexuality inherent in doll designs and raises questions about why such features are so prevalent. For more images, visit my Instagram account “StatsCop.”

The uncanny valley phenomenon is deeply intertwined with our psychological and social need for normalcy. In the early 20th century, German psychologist Ernst Jentsch introduced the term “unheimlich” to describe the uncanny. He suggested that experiencing something uncanny leaves one feeling out of place or disoriented, as if the object or situation is foreign. Jentsch highlighted that this feeling arises from encountering the uncertain or the undecidable.

Similar ideas were explored by French sociologist Emile Durkheim in the late 1800s when he discussed the concept of “anomie.” Anomie is often interpreted as a state of normlessness but better understood as insufficient normative guidance. During times of societal upheaval, individuals may struggle to identify what is expected or normal, leading to detachment and weakened social bonds.

This struggle for clarity is not a new phenomenon. Throughout history, humanity has sought to understand expectations and reality. Aristotle stated in 350 BC that the essence of a thing is its fundamental substance. Our quest for meaning, context, and the essence of existence has preoccupied philosophers for centuries.

Recent research by Miriam Koschate at the University of Exeter in 2016 revealed intriguing findings regarding our perceptions of highly humanlike robots. The study indicated that rather than focusing on their “almost alive” qualities, our brains associate these robots with thoughts of death, leading to feelings of eeriness. Interestingly, the study also found that adding emotional displays to humanlike robots can diminish the sense of uncanniness.

Reflecting on this, I was reminded of a 1995 Saturday Night Live parody commercial for Old Glory robot insurance featuring Sam Waterston. This humorous take on our fears regarding robots offers an entertaining perspective on the topic.

Chapter 2: The Role of the Outlier

Despite societal norms, there are individuals who defy expectations—renegades, mad geniuses, iconoclasts, artists, and even criminals. These figures challenge boundaries, provoke thought, and encourage growth. They compel us to either uphold traditions or adapt them. Like stones in a flowing river, they push against the banks, urging us to define our values and beliefs.