The Fate of Humanity: Learning from Dinosaurs' Legacy

Written on

Will we face a fate similar to the dinosaurs? If only we could be so fortunate. The truth is, dinosaurs endured far worse challenges than we do today. They navigated climate shifts and survived an asteroid impact, yet they thrived. In fact, paleontological evidence shows that dinosaurs are not entirely gone; birds are descendants of dinosaurs and they are quite remarkable in their own right.

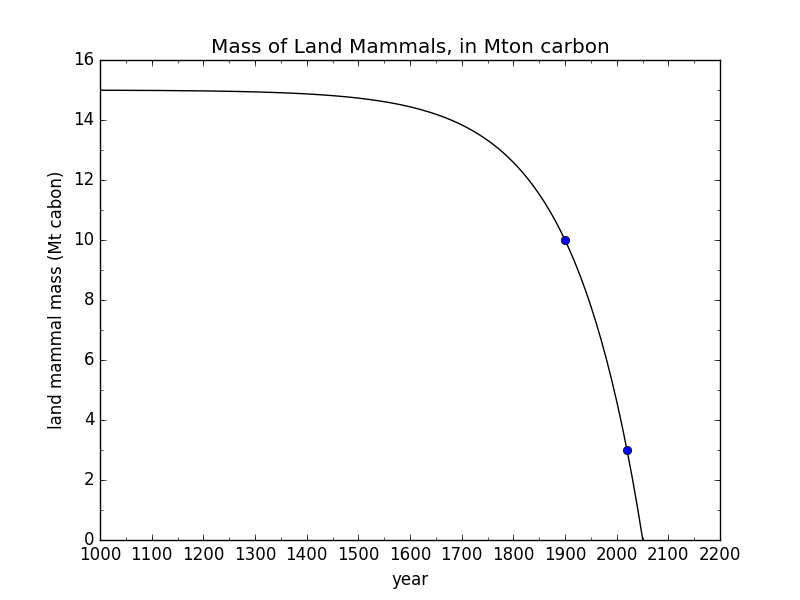

Mammals have coexisted with dinosaurs for eons, but it’s only recently that we’ve claimed any form of superiority. If one could even call it superiority when we’ve caused so much destruction to our own kind. Just look at how we’ve treated the Mammalia class:

From a geological perspective, we seem rather foolish. Dinosaurs outlasted us by a significant margin and didn’t self-destruct like we are now. It's not hard to imagine that they might one day sift through our remains. Our so-called civilization is merely another mass extinction event that dinosaurs are witnessing. We could gain invaluable insights from them on how to endure.

The Mistaken Extinction

The publication of The Mistaken Extinction in 1997 stirred controversy by suggesting that dinosaurs never fully vanished. While this idea is now widely accepted, the vernacular has yet to catch up. As paleontologist Julia Clarke notes, "birds are living dinosaurs, just as we are mammals."

The prevailing notion that dinosaurs went extinct while mammals flourished post-K/T event is misleading. Both groups survived, and it’s only in recent times that birds have become a punchline. Dinosaurs, in their many forms, still outnumber mammals. What we often mean is that the “cool” dinosaurs are gone, but that’s not entirely accurate. Throughout much of human history, birds resembled diminutive T. Rexes and were quite fearsome.

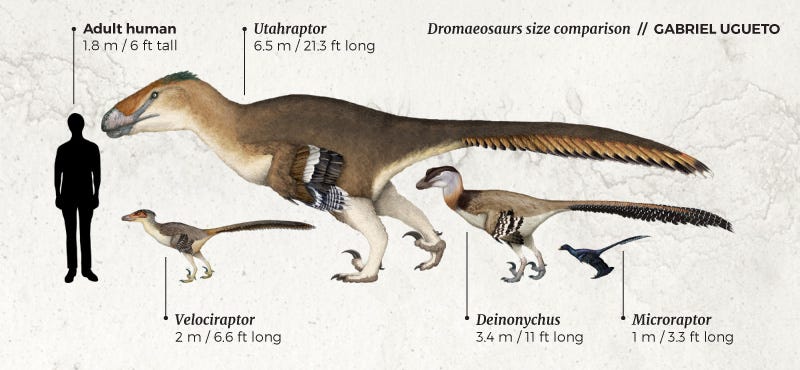

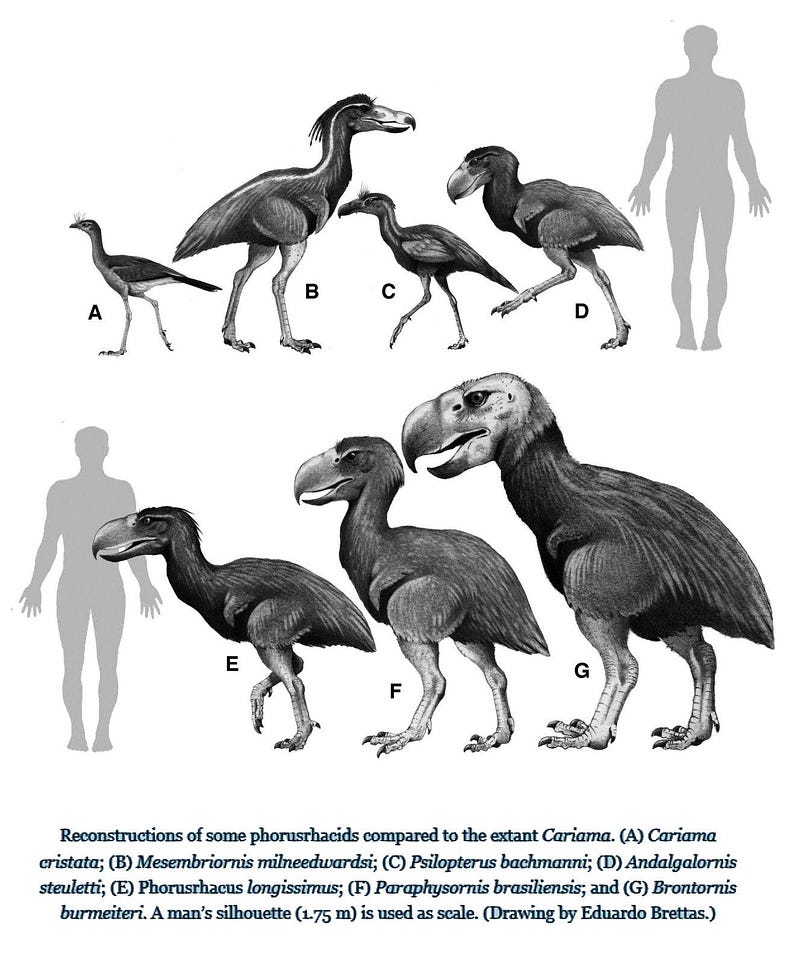

The enormous “Terror Birds” that roamed just a few hundred thousand years ago weren’t so different from Tyrannosaurus and were even larger than the Velociraptors that startled audiences in Jurassic Park.

After the age of the “terrible lizards,” smaller scavenger dinosaurs eventually gave way to “terror birds.” While these species may have been smaller, they were still formidable enough to terrify ancestral mammals.

Humans were fortunate to have evolved in Africa, away from these apex predators, until we developed tools. However, we coexisted with them. As Dingus and Rowe pointed out,

Possibly the most meaningful lesson gleaned from mapping dinosaur phylogeny is that our own history has overlapped with dinosaurs for about 20,000 generations, depending on what you choose to call a human.

They further elaborated:

It is a myth that theropods surrendered their role as top predator at the end of the Cretaceous, at least in some parts of the world. In South America and elsewhere, giant predatory theropod birds dominated terrestrial faunas for millions of years after the K/T boundary. Today, feathered raptors remain at the top of the food chain in many parts of the world, having inherited the role from some of their Mesozoic relatives.

Yet we still casually refer to dinosaurs as extinct. But what does that truly signify? The largest mammals have also vanished, yet we don’t generalize that to the entire group. Why should we do so with dinosaurs?

The “Terror Birds” certainly fit the popular image of a “badass dinosaur.” Just recently, an eagle snatched a village cat, challenging the notion that mammals reign supreme. While dinosaurs have indeed diminished in size following their environmental upheaval, they persist to this day. Even now, one could find themselves in a dangerous situation with a cassowary.

As Dingus and Rowe assert:

If current phylogenetic maps are correct, it appears that dinosaurs and our own primate lineage co-existed for a time span exceeding 70 million years. Both lineages survived whatever happened at the end of the Cretaceous. They further withstood the Pleistocene wave of extinction that surged across the globe. But following in its wake have come second and third waves, the second engulfing tropical islands [colonization] and the third now moving across the continents [capitalism/globalization].

Both of the Holocene waves have cascaded from the tragic symmetry between human population growth and the loss of biological diversity. The third wave of extinction has yet to reach its crest, and it probably won’t until after human population growth has peaked and begun to decline. By current estimates this is still a century away.

As noted in the latter part of this quote, while we obliterated the larger, more dinosaur-like flightless birds through colonization, we’re now annihilating everything through global capitalism. Dinosaurs, who have survived numerous extinction events, are currently living through a third one. Thus, the real question is not “will we end up like the dinosaurs?” but rather “where will we find ourselves alongside them?” In this regard, there is much to learn from our avian relatives, especially humility. This is a challenging lesson for humanity, who pride themselves on their “superior” intelligence while neglecting the wisdom of the dinosaurs and other creatures.

Our Foolish Evolution

In the pre-Darwinian era, history was neatly categorized into distinct ages, progressing from the Age of Fishes to the Age of Reptiles (Dinosaurs) and finally to the Age of Mammals. This linear progression implied that the best was saved for last. It’s essential to recognize that dinosaur fossils entered scientific discourse before the concept of evolution was established, leading many to argue that dinosaurs were created and subsequently extinct. As Dingus and Rowe highlight:

In the same paper in which Richard Owen coined their name [Dinosauria], he also claimed that dinosaurs are extinct, in an effort to disprove the idea of evolution. But with so much evidence linking birds and dinosaurs, why have so many evolutionists, from Huxley to Ostrom, agreed that dinosaurs are extinct?

The belief that dinosaurs are extinct is one of the great ironies of paleontology. Richard Owen is sometimes reviled for fighting throughout his life against evolution. Yet, even though modern science recognizes Darwin as the victor in this battle, the world did not go on to adopt a Darwinian view of dinosaurs. If Owen is looking down from the Hereafter, he must be gratified despite the bad press. Most people still accept his anti-evolutionary view, that dinosaurs are extinct.

The fossil record contradicts this notion. There are no distinct ages; dominance is merely a matter of timing. Mammals existed alongside dinosaurs, and dinosaurs never truly left their era. Evolution does not adhere to a concept of “progress”; it revolves around adaptation to an ever-changing environment.

Modern humans believe that intelligence grants us the ability to circumvent these challenges. The theory suggests that intelligence acts as a meta-adaptation, allowing us to adapt far quicker than biological evolution permits, thanks to technology. However, the results speak for themselves. After centuries of applying “intelligence,” we find ourselves in dire straits. As Forrest Gump famously stated, “stupid is as stupid does,” and we certainly appear foolish.

Humans have used what we term “intelligence” to become spectacularly maladaptive, creating chaos in our environment while claiming it’s merely economics. The so-called Homo sapiens have primarily utilized this intelligence for self-deception, believing that individual humans are paramount and that there are no limits to our aspirations. Those in authority seem to be less wise than children, who inherently understand the kinship of all living beings and the importance of treating them with respect. We are outsmarted by animals like cats, which instinctively clean up after themselves and show no admiration for human achievements.

It's debatable whether intelligence is a trait of great significance. While it may be impressive to our species, it holds little value in the grand scheme of things. We tout human intelligence as a tool for problem-solving, yet we’ve only created colossal issues.

Intelligence should enable better understanding and adaptation, yet we seem to have done the opposite. We’ve manifested our greed through corporations, utilizing technology to exploit our environment rather than adapt to it. Economists, often considered wise, fail to account for ecological realities, treating the environment as an endless resource to exploit, rendering us less intelligent than bacteria, who grasped this concept billions of years ago. Forget dinosaurs; we are less astute than pond scum.

Our grand narrative paints dinosaurs as creatures that relied on brute strength against nature and ultimately failed, while humans supposedly employ intellect and will prevail. This arrogance is crumbling. The evidence is clear, and the consequences are dire. We didn’t require an asteroid to bring about our downfall; it’s a result of sheer foolishness.

Who Survived?

Given that dinosaurs are our living ancestors and demonstrably wiser than us, what lessons can we glean from them?

Observing the day of the asteroid impact reveals which creatures survived and which did not. As Riley Black writes in The Last Days of The Dinosaurs:

Dinosaurs had evolved to match their habitat, and until now, Earth had changed slowly enough to let them adapt as needed. But this was too much for anything other than a bacterial extremophile to withstand. Caught out in the open — with no underground refuge or other shelter — most non-avian dinosaurs died within hours of the asteroid strike, no matter how near or far they were from the impact point.

The aftermath was catastrophic: searing air temperatures, earthquakes, tsunamis, and widespread fires. Anyone caught outside faced immediate peril, followed by a bitter chill as dust blocked sunlight and temperatures plummeted. These conditions were untenable for most life forms, yet some managed to endure. What can we learn from those survivors?

Riley Black notes that creatures capable of finding shelter — preferably underground or underwater — were more likely to survive the initial impact. Smaller, scavenging species fared better in the colder months that followed. Paleontologist Steve Brusatte echoes this sentiment in his book, The Rise And Fall of Dinosaurs:

The first thing we have to realize is that, although some species did survive the immediate hellfire of the impact and the longer-term climate upheaval, most did not. It’s estimated that some 70 percent of species went extinct. That includes a whole lot of amphibians and reptiles and probably the majority of mammals and birds, so it’s not simply “dinosaurs died, mammals and birds survived,” the line often parroted in textbooks and television documentaries. If not for a few good genes or a few strokes of good luck, our mammalian ancestors might have gone the way of the dinosaurs, and I wouldn’t be here typing this book.

This illustrates the need to dispel the misconception that mammals survived while dinosaurs did not. Many mammals perished, just as many dinosaurs endured. The real question becomes: what did the survivors have in common? Brusatte continues:

There are some things, however, that do seem to distinguish the victims from the survivors. The mammals that lived on were generally smaller than the ones that perished, and they had more omnivorous diets. It seems that being able to scurry around, hide in burrows, and eat a whole variety of different foods was advantageous during the madness of the post-impact world.

The critters at the base of their food chain ate decaying plants and other organic matter, not trees, shrubs, and flowers, so their food webs would not have collapsed when photosynthesis was shut down and plants started to die. In fact, plant decay would have just given them much more food.

Brusatte and Black highlight that being large and specialized became a disadvantage in catastrophic times. The dinosaurs that survived were the ancestors of modern birds, not the larger “Terror Birds” that evolved later. These early birds were smaller, capable of flying to safety, reproducing quickly, and consuming seeds that would outlast the harsh winter. In essence, the meek inherited the Earth, emphasizing the importance of adaptability.

Another significant lesson from the K/T extinction is our perception of geological time and the duration required for recovery after a catastrophe. Humans are currently allocating no time for recovery, an overly optimistic outlook. Brusatte notes that it took around 500,000 years for ecosystems to return to any semblance of normalcy at the onset of the Tertiary Age.

Already, a mere five hundred thousand years after the most destructive day in the history of Earth, ecosystems had recovered. The temperature was neither nuclear-winter cold nor greenhouse hot. Forests of conifers, gingkos, and an ever-increasing diversity of flowering plants once again towered into the sky. Primitive cousins of ducks and loons loitered near the lakeside, while turtles paddled offshore, oblivious to the crocodiles lurking underneath. But the tyrannosaurs, sauropods, and duckbills were no more, replaced by the sudden bounty of mammals that exploded in diversity when presented with an opportunity they had been craving for hundreds of millions of years: a wide-open playing field, free of dinosaurs.

Even Brusatte acknowledges the modern misconception surrounding dinosaurs, as he references birds in one context while dismissing them in another. The depth of this delusion is evident even in the titles of their works. However, what remains crucial is to understand the lessons we can derive from the trials faced by our ancient ancestors. What do these insights mean for us?

Who Will Survive?

The climate crisis we face today is neither as abrupt nor as catastrophic as the challenges the dinosaurs faced. This leads to several predictions. First, it is unlikely that humanity will face complete extinction. Like the dinosaurs, we have expanded into numerous (technologically aided) niches, many of which may endure, along with the requisite tools. Furthermore, given our numbers, historical evidence suggests that as few as 2,000 individuals could suffice to restart the population. Thus, while we may not go extinct, our current aspirations of “overcoming climate change” and colonizing Mars are unrealistic.

The lesson from the K/T extinction event is that we may survive, albeit in a significantly diminished capacity. In the aftermath of the dinosaur “extinction,” it’s notable that the larger, more complex species vanished. Thus, we should prepare to lose what appears to be our advanced complexity. However, appearances can be deceiving. Though we resemble ordinary apes, we have manifested our greed into expansive corporations, which I refer to as artificial life forms. This evolutionary phenomenon is not unprecedented; evolution has historically involved cells merging in early “mergers and acquisitions,” and life taking “artificial” forms is not surprising. Life continually emerges in ways that seem impossible, particularly to older life forms facing extinction.

These artificial entities, namely corporations, have embodied our greed and have been exploiting the planet since the 1600s. They have devoured larger flightless birds through colonialism and ravaged the environment through capitalism, contributing to the current collapse. In this context, ordinary humans resemble mere bystanders, scavenging off the remnants of their actions while trying to avoid being crushed.

Today, our ambitions have animated avatars that dwarf the dinosaurs. The expansive constructs we’ve created — nations, cities, corporations, factories, planes, and automobiles — are historically vulnerable. Large, complex beings are the least adaptable to rapid change, and our intricate societal framework is fragile. The ecosystem in which these artificial beings exist, termed “the economy,” is massive and unwieldy, much like the colossal dinosaurs, making it susceptible to catastrophic failure.

Unfortunately for us, climate change does not strike like an asteroid. The massive entities won’t simply collapse overnight; they will continue to trample us for another 50 years before succumbing under their own weight. It’s possible that their actions may wipe out humanity while leaving behind remnants like server farms humming in desolation.

Corporations are so entrenched and powerful that these artificial life forms might endure long after most natural life has perished. Like humanity, they have infiltrated various niches and require very few “stakeholders” to persist. They possess similar advantages, including limited liability. Corporations can essentially eliminate us while appeasing a handful of treacherous shareholders with imaginary currencies. This scenario is unfolding, and it may persist beyond what seems plausible. We find ourselves in uncharted territory where predictions often falter. Survival is a gamble, reliant more on luck than logic.

The only certainty is that rectifying our climate issues requires time. The recovery time post-extinction was 500,000 years, considered rapid for the dinosaurs. Before that, photosynthetic bacteria needed millions of years to restore balance. These durations are minuscule in evolutionary terms, but for us, 500,000 years would equate to 25,000 generations — a timeframe we are failing to acknowledge.

Today, “intelligent” individuals speak of “decarbonizing” and “capturing carbon,” as if the only flaw of our planet-consuming zombie is its unpleasant odor. Although it is indeed an issue, the underlying premise is existentially flawed. Given that our understanding of “intelligence” often lacks humility, we may need to learn the hard way, much like Icarus, who faced the consequences of his hubris.

As discussed, the notion of “overcoming” climate change is futile. It is too late, and the very concept of controlling nature is what led us to this predicament. A philosophical shift more akin to Isaac Asimov’s Foundation, preserving knowledge for future rebuilding while relinquishing imperial ambitions, may be necessary. Alternatively, one could think of it as Noah’s Ark, if a biblical reference is preferred.

In this context, “saving the world” looks less like constructing electric dinosaurs and more like sowing seeds for future scavengers. It demands a natural humility rather than artificial intelligence. It requires preparing for dramatically reduced circumstances instead of gearing up in our luxurious Teslas and indulging in video games. However, conveying this to Icarus, who is currently soaring high, may prove challenging.

Where Will We End Up?

The answer to the question of whether we will end up like the dinosaurs is ultimately inshallah. With hope, it’s a blessing worth praying for. Dinosaurs faced a level of climate change beyond our comprehension, yet they emerged alive on the other side. In a geological blink, they thrived once more. The common belief is that dinosaurs lacked intelligence, but they trusted the process and survived. In contrast, our celebrated intelligence has only hastened our decline. We have no right to look down on our ancient predecessors; rather, we should aspire to their wisdom.

We must not regard dinosaurs as mere poultry; instead, we should see them as elder cousins who do not bury their heads in the sand. That behavior is more characteristic of humans, who mistakenly believe that solar panels, silicon chips, or other sand-based solutions will save us. We cannot simply swap one finite resource for another while pursuing limitless ambitions on a finite planet. Stupidity manifests in our actions, and we have caused more destruction than any species in recorded history. Just ask any cat or animal; they are hardly impressed with us and often feel fear instead.

Homo sapiens may be irredeemable, but we are not beyond the possibility of a reboot, albeit in a form we may hardly recognize. If we wish to learn how to stand once more, we must first learn to kneel. We need to reconnect with ancient beliefs, respecting the old gods, trees, and animal spirits that we discarded in our blind quest for progress, all while neglecting the environment of which we are a part. Our ancestors understood this, but we, in our arrogance over our inventions, believed ourselves superior to them, to dinosaurs, and even to bacteria. Pride precedes a fall, and here we are, as foretold. Ultimately, we would be fortunate to end up like the dinosaurs. Inshallah.