The Colorado River Crisis: A Reckoning for 40 Million People

Written on

Chapter 1: The Colorado River's Dilemma

The Colorado River Basin is currently facing a slow-moving catastrophe, as highlighted by Kevin Moran, who leads water policy advocacy at the Environmental Defense Fund. "We are truly at a pivotal juncture," he remarked.

The Origins of the Crisis

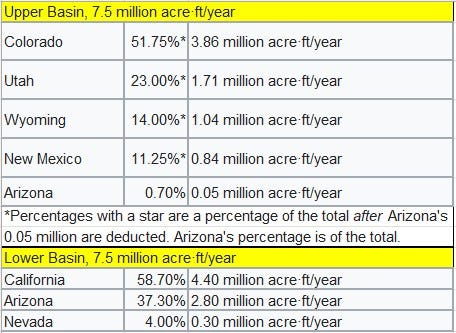

In 1922, delegates from the seven states dependent on the Colorado River convened for nearly a year at the Bishop’s Lodge in Santa Fe to draft the "Colorado River Compact." Their estimation pegged the river's annual flow at approximately 17.5 million acre-feet, leading to a division between the Upper Basin states (Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah) and the Lower Basin states (Arizona, Nevada, and California) at Lee’s Ferry, Arizona.

This allocation unfolded as follows:

The estimation was based on several particularly wet years between 1905 and 1922, with one year noted for its record flow of 24 million acre-feet. The Upper Basin was allocated 7.5 million acre-feet, and the Lower Basin received an equal amount. Subsequently, a treaty in 1944 with Mexico added another 1.5 million acre-feet to the Lower Basin.

During negotiations, delegates from the Lower Basin threatened to exit discussions unless they secured a more favorable outcome, resulting in the final million acre-feet being allocated to them, much to the Upper Basin's frustration.

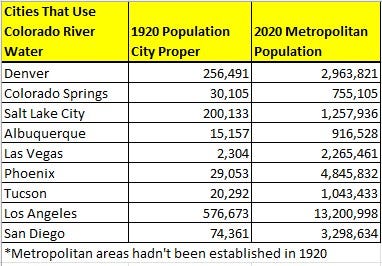

According to the Southern Nevada Water Authority, an estimated 1.5 million acre-feet of water evaporates from the river each year, a factor overlooked in 1922. Who could have predicted that the river would eventually support over 40 million residents in the rapidly developing Western region? The growth of cities in this area is notable:

Throughout the 20th century, the actual flow of the river averaged about 15.2 million acre-feet, falling short of the Compact's estimate. Today, climate change and persistent drought have reduced the flow to approximately 12.4 million acre-feet, with the past three years witnessing flows dip below 10 million acre-feet.

In 2022, significant reductions in water usage were implemented based on Lake Mead's levels, with 2023 necessitating further cuts of 2 to 4 million acre-feet. However, the states have failed to reach a consensus for the second time in six months. If an agreement isn't reached, the Interior Department will step in to enforce cuts, marking a historical federal intervention.

While the Upper Basin states assert they primarily rely on stream flow rather than reservoirs, drought has significantly reduced their ability to deliver adequate water downstream, cutting their contributions by nearly half. They argue that further reductions are not feasible.

This predicament leaves the Lower Basin states to shoulder the remaining deficit, which poses a serious challenge. Nevada, in particular, is unable to absorb much of the shortfall, as noted by John Entsminger, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority. They have already implemented some of the most stringent water conservation measures in the basin, currently receiving only 300,000 acre-feet of water annually from Lake Mead.

Arizona and California have long been at odds over Colorado River water allocation. Historically, California has consumed more than its fair share, using 900,000 acre-feet more than its allotment in 1952. Arizona has attempted to resolve this through legal channels, with the Arizona v. California case being one of the most drawn-out legal battles in Supreme Court history.

Moreover, Arizona is home to nearly thirty Native American tribes that possess senior water rights. Many of these tribes have been storing water in Lake Mead but are now beginning to withdraw their allocations to store in underground aquifers due to the ongoing drought.

Simultaneously, Arizona is experiencing significant population growth, with around 300 new residents arriving daily. The greater Phoenix area faces a housing shortage of approximately 100,000 units, yet developers persist in building amidst these challenges. (More details on Arizona's situation will be discussed in Part E of this series.)

Legal disputes and conflicts will likely intensify if the Interior Department makes decisions unfavorable to California, which historically has had priority rights to river water, totaling 4.4 million acre-feet annually. Although there have been periods of ample rainfall when California could "bank" water in Lake Mead, such occurrences are unlikely to happen again soon. A clause in the compact ensures that California receives its full allocation before any water reaches Phoenix or Tucson, known as the California Guarantee.

The future looks grim for this sunny region, and January 31 marks the looming date of reckoning. Stay tuned for further developments.

All articles in this series are intricately connected to the river. However, comprehending the entire picture can be overwhelming, with numerous stakeholders involved, including individuals and legislative bodies, some of whom may act deceitfully, while others advocate for environmental stewardship. If you're interested in delving deeper, I recommend reading "Cadillac Desert." Meanwhile, I will strive to connect each segment cohesively, attempting to clarify this complex issue.

Next up: The Colorado River, Start to Finish

Sources include: * “As the Colorado River Shrinks, Washington Prepares to Spread the Pain” by Christopher Flavelle in the New York Times, 1/27/2022 * Arizona Republic, 12/21/2022 * U.S. Census Bureau * Wikipedia * “Cadillac Desert” by Marc Reisner

I write about other topics beyond the ongoing megadrought!

The Colorado River Crisis: A Visual Overview

This video titled "40 Million People Rely on the Colorado River, and Now It's Drying Up" explores the impact of the drought on the millions who depend on this vital water source.

The Legal Landscape of Water Rights

In this documentary, "Colorado River in Crisis: A Los Angeles Times documentary," the complexities of water rights and the ongoing crisis are vividly depicted.