The Cat: An Invasive Species and the Complexity of Home

Written on

I tend to shy away from situations where I'm completely lost. Do you?

Since relocating to Tulsa, Oklahoma, in April, I've felt quite overwhelmed. The home purchase was somewhat unexpected, involving a larger sum than I ever anticipated saving, and I had never even visited Tulsa prior to becoming a homeowner. When asked about my decision, all I could say was, "Uh, I don’t know, it just felt right."

Soon after settling in, I faced plumbing issues and a lengthy wait for appliances, only to hit the road for my first half marathon. Unfortunately, I discovered a genetic foot issue that left me in tears during the last third of the race. Upon returning to Tulsa, I left again shortly after for a friend's wedding, and ended up with a painful eye infection. Driving back to Tulsa with one eye nearly shut after a grueling 17-hour journey, I realized that I had already begun to consider this place my home.

One of the most challenging aspects of moving into my first house after years of apartment living has been managing the yard. I've previously shared my unexpected pride in mowing my quarter-acre lot and dealing with sewage issues that arose shortly after my return. The task of mowing, while relentless, felt manageable. I had experience, albeit limited, and I knew I could do it again! Could I afford a lawnmower that would simplify the job? Not at all. Yet, I found joy in the labor, savoring the scent of freshly cut grass and the growing familiarity with my little patch of land.

As I concentrated on mowing, the flower beds in front of my house sparked both admiration and trepidation. I had no idea what plants were thriving there, and I couldn't fathom how to care for them. I avoided those beds, feeling a mix of curiosity and insecurity. After a heavy rain, I marveled at the sudden appearance of new leaves and blooms. When I noticed a bush wilting, I poured water around it, realizing I'd eventually need to purchase a hose.

The grass continued to grow rapidly during the early summer months, and I struggled to keep up. My neighbor reassured me that growth would slow in July, which turned out to be accurate. With the extreme heat and the onset of a drought, I found more time to observe the flower beds. I noticed long, spindly vines that had sprouted, the pansies succumbed to the sun, and fresh grass emerged from the mulch. I pondered the need to weed the garden but had no idea how to distinguish between weeds and non-weeds. In fact, I'd always dreamed of having a house adorned with vines, reminiscent of a romantic Italian villa—right in the heart of Oklahoma. Perhaps I should simply let everything grow and see where it leads!

According to Wikipedia, an invasive species is "an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment." My front yard was beginning to resemble a green-vined monster, far from the idyllic seaside villa I envisioned. Was that a tree sprouting or merely tangled vines? I couldn't tell.

Today, I finally confronted my fears. Armed with a plant-identification app, I learned about a native tree that had been growing taller each week since my arrival. I discovered a flowering vine from Southeast Asia—an invasive species that, while beneficial for pollination in certain contexts, poses a danger to animals and humans. I also identified various native and nonnative grasses, which my neighbor's cat loved to roll around in after I removed a toxic weed that had started to engulf the grass beneath its twisted vines. With my hori hori knife, I dug into the mulch and soil, cutting away roots and creating piles of leaves and dead grass. It felt transformative to see some plants clearly again, almost like giving the Earth a haircut.

Part of my reluctance to tackle this task stemmed from my fear of causing accidental harm due to ignorance—a fear that extends into other areas of my life. I felt the need to wait, observe, and understand more before uprooting anything.

One of my motivations for moving to Oklahoma was the desire for a place where I could afford to live and foster a deeper connection to the land. I wanted to explore my interest in gardening and discover what I could learn through that process.

Today, I was reminded of the long days spent outdoors as a child, collecting branches and stripping bark from them. I sweated in the summer heat, just like I did back then—soaking wet and dizzy. I could feel my heart racing, and I smiled at the cat rolling in the grass beside me, wondering if I had made a mistake taking on this extra work alone. Yet, my body insisted that this was just what I needed. Keep going.

I've always viewed invasive species negatively. I know they are often unintentionally introduced to ecosystems due to travel or industrial activities, posing health risks to native flora, fauna, and even humans.

National Geographic states, "To be invasive, a species must adapt to the new area easily. It must reproduce quickly. It must harm property, the economy, or the native plants and animals of the region."

Whenever I have lived outside my hometown, I've worried about being like an invasive species—acutely aware of my potential contribution to gentrification in my neighborhood and the broader city context, while also grappling with the definition of being "from" a new place. Ironically, one reason I chose not to return to my hometown was that I felt priced out, even with a decent remote job on the West Coast. The rising cost of living feels particularly painful when it occurs in a place that should remain accessible for you and your family.

The reality is that colonialism has rendered all of us non-indigenous individuals akin to invasive species—taking root, reproducing rapidly, and potentially harming property, the economy, and native beings in our quest for survival until a stronger force eventually uproots us.

Just this past Friday, over 800 individuals embarked on an eight-day expedition through the Florida Everglades, seeking invasive Burmese pythons for cash.

Since 2000, more than 17,000 pythons have been removed from the Everglades ecosystem, according to a news release. Burmese pythons, which are not native to Florida, prey on birds, mammals, and other reptiles. A female python can lay as many as 100 eggs a year.

Experts are uncertain whether tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of pythons are decimating the Everglades ecosystem due to the challenges of conducting surveys in the area. Once a popular exotic pet in the 1980s, the pythons likely proliferated after Hurricane Andrew devastated the region in 1992, along with a python breeding facility.

Recently, a Polish scientific institution classified domestic cats as "an invasive alien species" due to their adverse effects on wildlife and bird populations, sparking outrage among cat enthusiasts globally. I found this particularly amusing, especially after removing invasive weeds from my garden while the neighbor's cat looked on.

In recent years, ecologists have begun to uncover how new species might offer shelter and assist other plants in adapting to climate change challenges. As with many topics, the complexities depend on one's perspective and the narrative surrounding what it means to be native or an outsider. As a Times writer notes,

Whether a species is viewed as native often depends on when you arrived on the scene. Much of what Americans consume was originally imported: The horse, an emblem of the American West, was reintroduced by the Spanish thousands of years after the original North American horse went extinct. Several states designate the honeybee as their state insect. But like many state fish, insects, and flowers, bees are indeed immigrants.

In at least one instance, a species that had long been extinct in its original range was considered an interloper upon its return.

While this may be true, we must also acknowledge that invasive grasses contribute to catastrophic wildfires worldwide. While one invasive species may offer protection or at least not completely devastate an ecosystem, another could lead to the extinction of an entire species. The cognitive dissonance I experience regarding this knowledge and its implications for other aspects of our existence on this uncertain and vulnerable planet overwhelms me.

When I find myself consumed by the paradoxes and intricacies of life on Earth, I often turn my thoughts to the stars. Contemplating space and its vastness brings me an unexpected sense of tranquility.

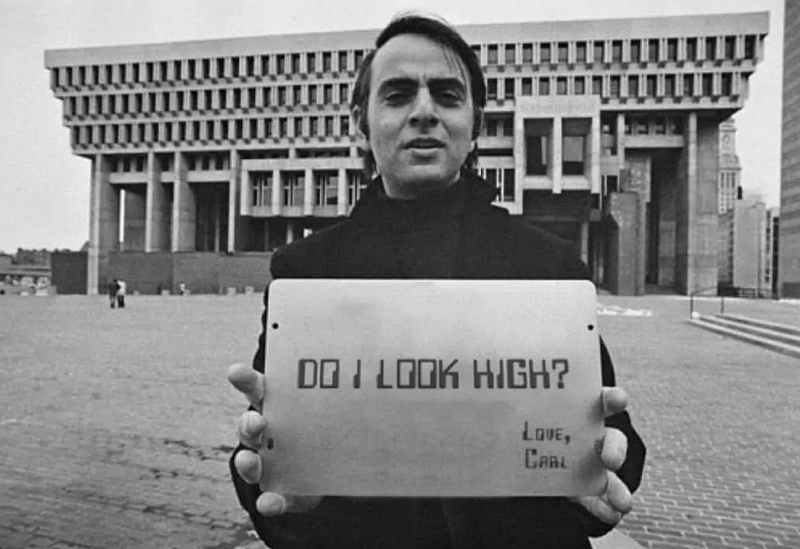

Carl Sagan once stated,

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction