The Boundaries of Science: Examining Carnap's Perspective on Scientism

Written on

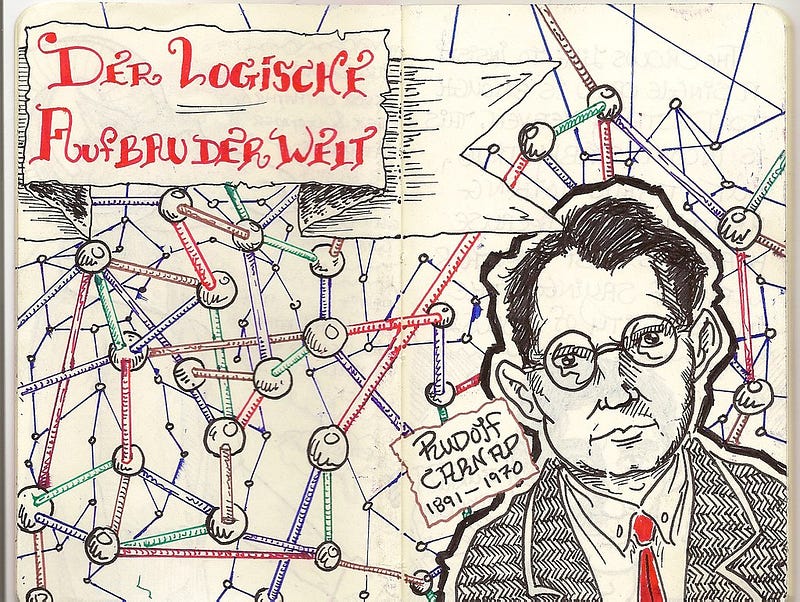

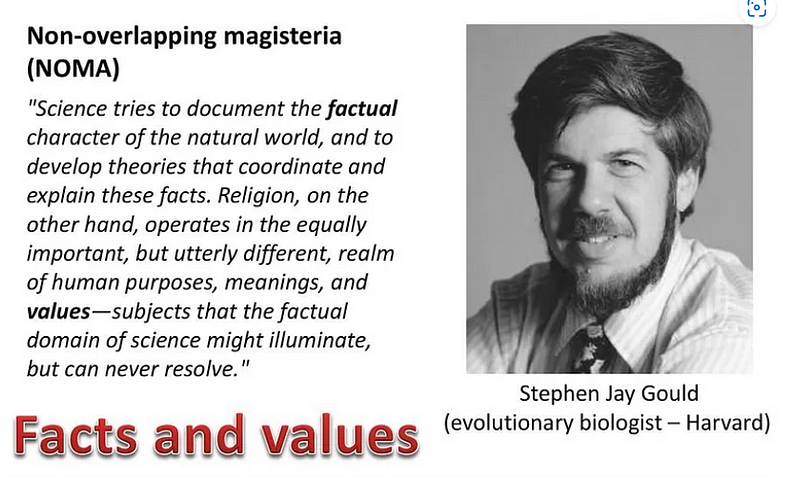

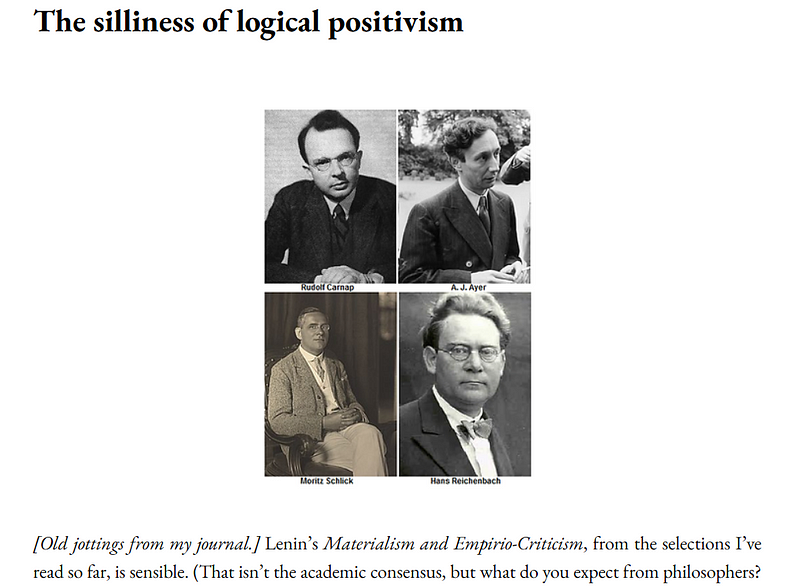

Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970), a prominent logical positivist, asserted that the realm of science is boundless. His viewpoint embodies what critics have labeled scientism. It is essential to note that "scientism" is frequently employed as a derogatory term. This essay delves into the extent of science's reach and questions whether many non-scientific inquiries—particularly those that provoke debate—can ever truly be resolved. In essence, are numerous religious, philosophical, aesthetic, and ethical inquiries beyond reach? Or do my reflections on these inquiries signify a shift towards a new form of logical positivism?

“When we assert that scientific knowledge is boundless, we imply that there is no question that science cannot, in principle, answer.”

— Rudolf Carnap

Many individuals are taken aback by Carnap's stance, or similar perspectives voiced by other philosophers and scientists. Even some philosophers express disbelief. For instance, William P. Alston, in his paper ‘Yes, Virginia, There is a Real World,’ criticized the notion that scientific knowledge is the sole form of knowledge, labeling it “outrageous imperialism” to assert that only the sciences can address certain pertinent queries.

Conversely, a considerable number of individuals enthusiastically endorse Carnap's viewpoint, albeit in varying degrees. Ultimately, the opening statement succinctly encapsulates a logical-positivist perspective, as articulated in the late 1920s, specifically in Carnap's 1928 work Der logische Aufbau der Welt — The Logical Structure of the World. His assertions also embody what many currently interpret as scientism.

“When it is said that many scientists revere science as a religion, or that they exhibit dogmatic and fundamentalist tendencies, one can see a recurring theme. Skeptics might interpret this as mere projection or juvenile tactics, accusing opponents of the very behaviors they themselves exhibit.”

The frequent citation of Carnap's remarks relates predominantly to the concept of scientism, leading to their appearance in various works, including Scientism: Science, Ethics and Religion and Science Unlimited?: The Challenges of Scientism. It appears that these authors have often encountered Carnap's statements through other critiques of scientism rather than directly from his original text.

This reliance on a passage from 1928 to represent a scientistic stance seems peculiar. (Refer to the concluding section of this essay for more retrospective critiques of logical positivism.)

Science’s Boundless Domain?

To summarize this essay's interpretation of Carnap's assertions: he claimed that scientific knowledge is “unlimited.” His definition underscores the idea that “no question exists whose answer is, in principle, unattainable by science.” This posits an unrestricted role for science, suggesting that no inquiry lies outside its purview.

However, Carnap's stance requires clarification. While there are numerous queries that science cannot resolve, this limitation stems from their inherent nature—some questions may be inherently unanswerable. Simply put, any answers beyond scientific inquiry remain unconfirmed, untested, and unverifiable, rendering them inconclusive. This inconclusiveness is what ultimately leads such questions to be considered beyond science.

Some critics of scientism may recognize this limitation, acknowledging that the questions unaddressed by science may not be resolvable by other fields either. However, this is not the prevailing belief. Many assert that their chosen worldview—be it religious, philosophical, or theoretical—can indeed provide answers where science cannot.

But can we genuinely verify that an answer has been supplied by these non-scientific domains? History suggests otherwise. Hence, answers provided by such disciplines often remain contentious.

This dilemma extends to many—if not all—religious, philosophical, political, and aesthetic responses to inquiries outside the scientific realm. Nevertheless, this is not solely a scientific perspective on potentially unanswerable questions. Various methods exist to engage with this topic.

Consider the American philosopher Gordon Park Baker (1938–2002).

In his work ‘?????????: ????? ??? ?????’ (found in Philosophy in Britain Today), Baker observed:

“We should make substantial efforts to question what is typically considered genuinely philosophical. Often, the correct responses to such inquiries may, paradoxically, be further questions!”

Numerous inquiries have been regarded as profound and deserving of thoughtful consideration, often categorized as “beyond science.” Thus, it is equally important—if not more so—to examine these inquiries critically. As Baker aptly put it:

“The unexamined question is not worth answering.”

Baker further elaborated:

“To accept a question as coherent and then to build a philosophical framework around it represents a crucial step in the entire inquiry.”

Notably, these insights do not stem from a scientific perspective; they lie outside the realm of science. In this respect, Baker's views certainly do not align with scientism.

Perhaps these particular questions about questions possess a Wittgensteinian quality. Baker makes additional Wittgensteinian observations in the following statement:

“To assume that philosophical questions await concrete answers presupposes that the questions themselves are coherent and require responses (which are not already available). Why should this not be a suitable subject for philosophical examination?”

Carnap and fellow logical positivists, well before Baker, believed that such non-scientific inquiries warranted philosophical exploration. Since then, they have attracted scrutiny from various philosophers.

If Not Science, Then What?

Recall Carnap's assertion that “there is no question whose answer is, in principle, unattainable by science.” Therefore, if it is argued that some answers elude scientific inquiry, which discipline, philosophy, theory, or individual can provide those answers?

The answer may vary depending on the specific question or context.

For instance, would we expect scientific inquiry to address the following trivial example?

> What is the greatest rock song of all time?

Or:

> What is the true religion?

More critically:

> Is war ever justified?

It is clear that science cannot resolve these inquiries. This may be due to the possibility that no definitive answers exist. That said, scientific data, arguments, and evidence can contribute to the discussion. Yet, these alone will never yield a satisfactory answer.

Specifically, which data or evidence would confirm what constitutes the greatest rock song of all time? While some may present certain facts to bolster their claims, these facts alone do not determine the answer.

For example, if someone argues that ‘Making Your Mind Up’ (by Bucks Fizz) is the greatest rock song because it achieved the highest sales, this merely presents a stipulative definition. There is no obligation for others to accept this interpretation of the greatest rock song ever.

Others will define the greatest rock song ever according to different criteria and standards. However, these alternative definitions also lack conclusiveness.

This illustrates why science struggles to provide resolutions for such questions. The issue is not that these questions “transcend science” in some obscure way. Instead, it is that, fundamentally, there are no answers. Consequently, the absence of definitive answers leads to the perception that such questions lie beyond science. It is not a matter of answers being available but rather that no genuine answers exist.

Alternatively, numerous individuals will propose various answers to these inquiries, yet none can be substantiated as true or even correct.

The same applies to the question, “Is war ever justified?” Beyond its general nature, it is presumed to transcend science not merely because it pertains to philosophy, religion, ethics, or morality. It transcends science because no empirical tests, evidence, or observations could provide a conclusive response. Again, there are multiple answers that many individuals will give, but none can be validated as true.

Thus, in these instances, it is not that certain questions belong to domains outside of science due to some indefinable quality. Rather, it is that no authentic answers will ever emerge, regardless of which religious leader, philosopher, or theorist claims to possess the answers.

In context, Carnap's initial statement requires broader consideration.

You Needn’t Be a Carnapian or a Logical Positivist

It is important to clarify that the preceding analysis does not serve as an unqualified defense of Rudolf Carnap's logical positivism. Indeed, both Carnap's perspectives and logical positivism as a whole are not without issues.

Is this surprising?

For instance, many find Carnap's view on the limited role of philosophy somewhat unappealing. The same can be said for Wittgenstein's philosophical stance from the 1920s until his death in 1951. Similarly, Carnap's thoughts on the “immediately given”—once viewed as the bedrock of science—appear somewhat antiquated today.

Perhaps most philosophical positions from the 1920s now seem outdated. Likewise, many philosophical viewpoints from today may seem dated by the early 22nd century—and likely well before that!

Moreover, other philosophical movements and perspectives from the 1920s onward face their own challenges. Just as many individuals critique various movements and positions from that era, so too do those who once embraced logical positivism critique its shortcomings.

To summarize, the writings and assertions of the logical positivists from the 1920s to the 1940s are meticulously examined by self-proclaimed advocates of anti-scientism. For these critics, it appears as though logical positivism stands as the sole philosophical movement that made missteps and proposed disputable claims.